Key Points:

- Study explores risk factors for perforator stroke after basilar artery angioplasty and/or stenting for symptomatic atherosclerotic stenosis

- Diabetes, duration from last symptom to procedure, and pre-procedure stenosis identified

Patients who undergo basilar artery angioplasty and/or stenting are more likely to develop perforator stroke if they are diabetic, have a shorter gap between the time from last symptom to their procedure, and had less severe baseline stenosis. The predictors, culled from a single-center, retrospective analysis, were published online July 7, 2016 ahead of print in the Journal of NeuroInterventional Surgery.

Charles Prestigiacomo, MD, of Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, (Newark, NJ) and president of the Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery (SNIS), told Neurovascular Exchange in a telephone interview that perforator stroke has been a longstanding bugbear for neurointerventionalists.

“Trying to understand factors that can contribute to . . . the incidence of perforator stroke and ways to manage it is exactly what we need,” Dr. Prestigiacomo said. Avoidance is key, he added, since treatment of the complication is limited and outcomes are often poor. In addition, the findings of this study may be relevant to the risk of perforating vessels when stenting the anterior circulation.

Zhongrong Miao, MD, of Beijing Tiantan Hospital (Beijing, China), and colleagues retrospectively assessed 255 consecutive patients undergoing basilar artery angioplasty and/or stenting for symptomatic atherosclerotic stenosis at their center. They analyzed multiple variables, including demographic data, risk factors of atherosclerosis, symptoms, characteristics of imaging, and procedure factors to determine which were associated with perforator stroke.

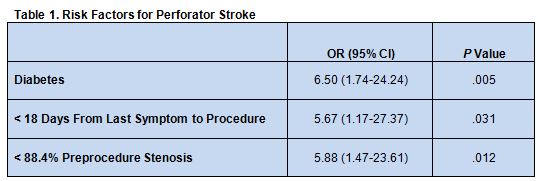

Overall, perforator stroke was identified in 13 patients (5.1%). Multivariate analysis revealed that the presence of diabetes, less than 18 days from the last symptom to the procedure, and less than 88.4% preprocedure stenosis were all significantly linked with perforator stroke risk (table 1).

A Rationale Behind Each Risk Factor

The investigators write that “perforator infarction associated with intracranial angioplasty or stenting was most likely caused by the atherosclerotic debris being displaced over the perforator ostium during the procedure. Diabetes has been proven to be a risk factor of small vessel disorder. We speculate that patients with diabetes are more likely to have potential perforator branch disease and are therefore more susceptible to ostial occlusion.”

Regarding stenosis < 88.4% as a risk factor, they say a “possible explanation is that symptoms of patients with less severe stenosis are less likely to be caused by the hemodynamic deficiency and they are more likely to have perforator disorders. A reasonable method to confirm this assumption may be using high-resolution MRI to demonstrate the perforator branch status.”

Dr. Prestigiacomo said the presence of these unmodifiable risk factors should not exclude patients from angioplasty or stenting. Rather, knowledge of their impact can help guide decision-making and conversations about risks and benefits with patients and their families. “It’s important for stratifying the risk but not necessarily for eliminating or excluding patients from treatment,” he said.

With regard to time from last symptom to procedure, the authors write that this finding is consistent with previous studies. “It has been suggested that atherosclerotic plaque tends to be unstable when treatment is close to symptom occurrence and therefore more susceptible to mechanical deformation or impaction during the procedure,” they say.

While it stands to reason then that the procedure should only be performed after the acute phase of ischemic stroke, write the authors, they point out that a post hoc analysis of the SAMMPRIS trial did not reveal a difference in complication rates with delayed treatment.

But Dr. Prestigiacomo said that SAMMPRIS did reveal a trend toward worse outcomes for patients treated within 7 days, so the issue of delaying treatment remains an important topic of inquiry. He is a site investigator in the WEAVE trial, which is looking specifically to ensure that stent placement does not occur during the acute stage of disease.

“There are some data suggesting that waiting might be better,” he said, adding, “If the patient has out-of-control diabetes, one argument might be to . . . get them at their best possible levels, if it is clinically feasible to wait. . . . You can [also] tell them to stop smoking and get their blood pressure under control.” But in some cases, he added, waiting is simply not an option.

Moving forward, Dr. Prestigiacomo recommended the issue can best be studied further through a large, multicenter national or global registry trial rather than a randomized trial. “These cases are going to be few and far between,” he said. “Not all patients will qualify for [stenting or angioplasty]. This is high risk, so you want patients who have been medically refractory for a number of issues [and cases where] you have maximized medical therapy first, you have taken care of all the comorbidities, and you have waited some time.”

Source:

Jia B, Liebeskind DS, Ma N, et al. Factors associated with perforator stroke after selective basilar artery angioplasty or stenting. J NeuroInterv Surg. 2016;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures:

- Dr. Miao reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Dr. Prestigiacomo reports being on the advisory board for Stryker, founding editor of the Journal of NeuroInterventional Surgery, and medical director for patient safety at the SNIS.