Women, black patients, and those living in West Central Florida were most affected by delayed care.

There remains room for improvement in the timely delivery of IV tPA to eligible stroke patients, especially certain vulnerable populations, according to an analysis of data out of Florida and Puerto Rico. The findings were published in the August 2017 issue of Stroke.

This analysis is the “first to address this quality metric in stroke care in a large registry in Florida and Puerto Rico, US regions with a large proportion of minorities” lead author Tatjana Rundek, MD, PhD (University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL), told Neurovascular Exchange in an email. “The network of hospitals that we have developed during this project is a valuable source for future studies and planning of interventions to improve stroke care and reduce health disparities. Our registry represents a potential quality improvement model for the whole Florida state.”

Rundek and colleagues analyzed data on the 6,181 patients (9.4%) who were treated with IV tPA out of a total of 65,654 patients admitted between 2010 and 2015 with acute ischemic stroke and included in the Florida-Puerto Rico Collaboration to Reduce Stroke Disparities (FL-PR CReSD) study.

Overall, 42% of the IV tPA-treated patients received it within 60 minutes and 18% within 45 minutes. After adjustment, women were found to be less likely than men to receive IV tPA within 60 minutes (OR 0.81; 95% CI 0.72-0.92) or within 45 minutes (OR 0.73; 95% CI 0.57-0.93). In addition, during off-hours, black patients were less likely than white patients to receive IV tPA within 45 minutes (OR 0.68; 95% CI 0.47-0.98).

There were also regional variations. Patients treated in South Florida had the highest rates of timely treatment, with 50% of patients treated within 60 minutes and 23% treated within 45 minutes. The lowest rates occurred in West Central Florida, where only 28% were treated within 60 minutes and 11% within 45 minutes.

Individual-, System-Level Factors

“Our results indicate that there are some individual-level factors and some system-level factors . . . that need to be addressed to reduce these disparities and increase the number of acute stroke patients receiving tPA in a ‘golden time window,’” Rundek said.

She speculated on reasons for the observed disparities, such as certain patients taking longer to seek care, being less likely to arrive at hospital via emergency medical services (EMS), having atypical stroke symptoms, or being less likely to recognize stroke symptoms.

In some types of patients, these factors may cluster. Black patients may on the whole have a lower socioeconomic status plus be less likely to arrive by EMS and less apt to recognize stroke symptoms and call 9-1-1, she explained. They are also more likely to have poor blood pressure control, necessitating treatment prior to initiation of tPA. Women, meanwhile, are more likely to be taking anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation, which can also impede tPA use.

Mary Sarrazin, PhD (University of Iowa and Iowa City VA Medical Center), told NVX in an email that the findings mirror those of other studies examining disparities in delivery of time-sensitive treatments. “For example,” she said, “older studies showed significant racial and gender disparities in the time from hospital arrival to receipt of percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction.”

Sarrazin believes patient behaviors that delay hospital arrival are most likely to affect access to tPA, since it is a time-sensitive treatment. But disparities in door-to-treatment time among patients who received tPA “are best explained by what goes on within the healthcare system, and may reflect such things as the availability of off-hours specialists or comprehensive stroke care at the receiving hospital, or use of advanced EMS services,” she said.

Paths to Improvement

Sarrazin suggested that the disparities can be addressed via “a strategy targeted to educating patients and families about signs of stroke and best procedures for engaging the health system when a stroke is suspected.

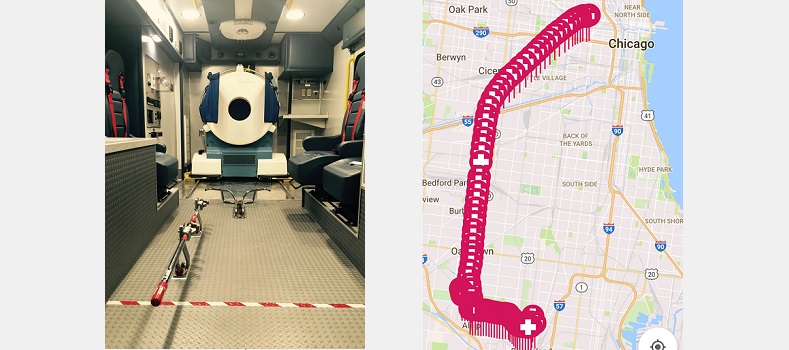

“A separate strategy may be required to better serve patients once they seek care,” she continued. “For example, prior to administering tPA, clinicians must first confirm the diagnosis of stroke, and second rule out contraindications to tPA. Technology such as telemedicine may help hasten the occurrence of these events. In addition, greater availability of advanced EMS services with the capability of administering tPA may help improve timely treatment for patients who lack geographic access to comprehensive stroke centers.”

Rundek had similar recommendations, echoing Sarrazin’s suggestion to step up patient education about identifying stroke and seeking emergency help. She also suggested that hospital systems of care can be adjusted to speed up delivery of IV tPA, such as reducing time to CT by having it available in or near the emergency department and by prepreparing stroke packets with orders ready. IV tPA can also be initiated while the patient is still in the scanner, she noted.

“In addition to reducing the observed disparities, we may need to do better with risk factor control in lower [socioeconomic status] communities and specifically target ‘vulnerable’ populations,” Rundek commented. “In addition, after hospitalization for acute stroke, we need to do a better job in transition of stroke care to prevent stroke recurrence and more disparities in stoke outcomes.”

Source:

Oluwole SA, Wang K, Dong C, et al. Disparities and trends in door-to-needle time: the FL-PR CReSD Study (Florida-Puerto Rico Collaboration to Reduce Stroke Disparities). Stroke 2017;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures:

Rundek and Sarrazin report no relevant conflicts of interest.